Highline Schools continue to blaze trails where Seattle's stand idle

/Once upon a time back in 2011, Susan Enfield was the interim superintendent of Seattle Public Schools. Just when it looked like Seattle might hand her the job on a full-time basis, Enfield said she didn't want the gig. She withdrew her name from consideration -- not because she didn't want to be a superintendent, but because she didn't want to be a superintendent in Seattle.

Soon after, she was chosen to steer the ship for Highline Public Schools, a smaller district just outside Seattle with less-dysfunctional governance. Since that time, Highline Public Schools have repeatedly taken bold steps in the name of equity, addressing hard truths and implementing innovative programs and solutions in an earnest effort to make meaningful change.

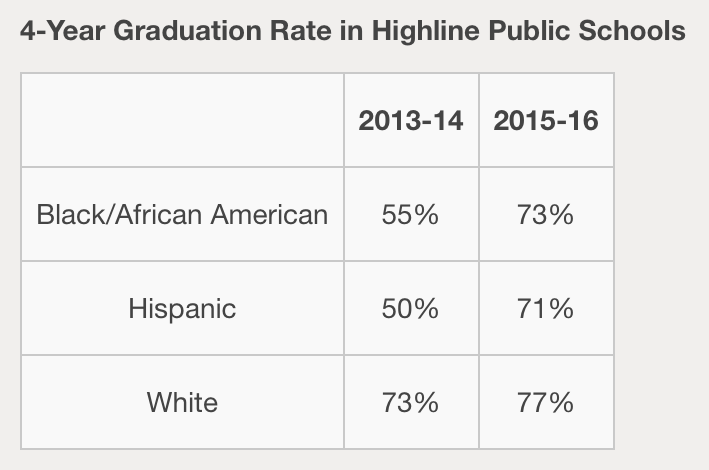

The results so far have been remarkable. District-wide graduation rates grew from 62.5 percent in 2012 to 74.8 percent in 2016, but the graduation-rate gaps along racial lines have all but closed:

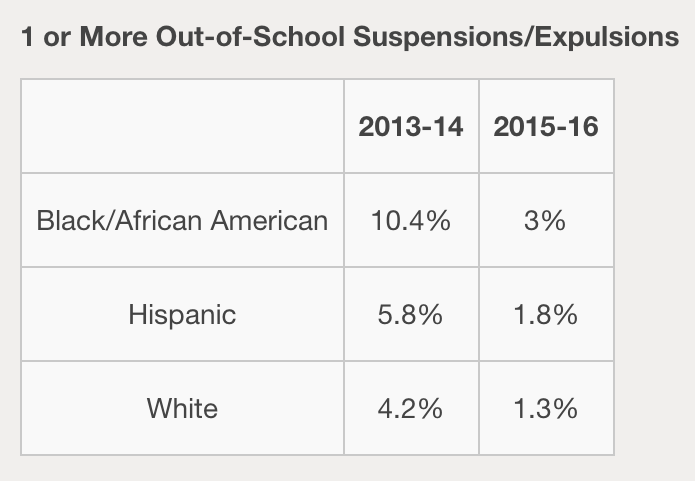

Highline's discipline rates have seen a similar trajectory, with out-of-school suspensions and expulsions dropping to 682 in 2017 from 2,117 in 2012. But again, even more impressive is that the disproportionality in the district's discipline rates is quickly disappearing:

Seattle's schools, meanwhile, have languished in the unacceptable status quo, which includes problems with disproportionate discipline along racial lines and the fifth-worst achievement gap in the nation. Jose Banda, who took over as superintendent after Enfield's departure, didn't last two years and could not have been more pointless. Larry Nyland has been fine but uninspiring.

How did we get here? How did "progressive" Seattle manage to lose a thrilling talent like Enfield to a formerly hole-in-the-wall district like Highline?

Neal Morton wrote a story recently for the Seattle Times about a new program in Highline aiming to get more bilingual teachers into classrooms that's getting well-deserved attention nationally. While primarily focused on the forward-thinking, equity-minded pathway to teaching that Enfield's district has created, Morton's article touches on a number of the deep-seated issues that have led to the strange, nuanced tapestry of disparities between Seattle and Highline.

For one thing, it's important to know that a primary reason Susan Enfield left Seattle Public Schools is the utter dysfunction of the Seattle School Board. She has never, to my knowledge, acknowledged this publicly, but it's the truth. Chris Korsmo, CEO of the League of Education Voters, even said as much when Enfield announced she was leaving SPS nearly six years ago. Korsmo told the Seattle Times at the time that she knew Enfield might withdraw from the hiring process because "it was clear that the revamped School Board, which held its first meeting last week, would likely try to control more of district operations than Enfield may have been comfortable with."

That means Seattle schools' problems run so deep, and are so inexplicably supported by voters, that we can't even attract and retain the type of leader who might be able to help us solve them. And it's gone beyond just top-level leadership. Seattle has been hemorrhaging bold, equity-minded staff for years now. Many, not surprisingly, are ending up in Highline.

Take Jonathan Ruiz Velasco, for example, who's the focus of Morton's story for the Times. Ruiz Velasco worked for five years as a bilingual instructional aide at Bailey-Gatzert Elementary in Seattle's Central District. When he decided he wanted to become a teacher, however, Ruiz Velasco had to look outside of Seattle Public Schools to find an appropriate pathway into the classroom. He ended up as part of "a new program in Highline Public Schools, where bilingual paraeducators can tap state-funded scholarships to help them earn teaching certificates."

Seattle has fewer alternative pathway options for educators because the teachers unions, in conjunction with a misguided school board, have blocked the establishment of such pathways at every turn, working to discredit and disallow anything different than traditional teacher education and certification.

Teach For America's arrival in Seattle in 2011, for example, drew such fervent opposition that eager young teachers were targeted with vicious online attacks. Several had their personal information posted online, which led to a break-in and robbery for three teachers sharing a house, and to a dangerously compromised restraining order against a past abuser for another young woman.

The school board, too, made ridding Seattle of TFA one of its primary missions, and dealt aggressively and callously with the organization as it tried to make inroads. As a result, while TFA is flourishing in most of the state, especially in eastern Washington where politics and acknowledged needs are different, the organization does not currently place teachers in Seattle Public Schools because of the hostile climate -- meaning another alternative pathway to certification is unavailable in the state's largest district, and another potential partner was treated like an enemy.

Seattle is a "progressive" city in many ways. We can all gleefully smoke weed and marry whomever we like, but if you start talking about public education in a way that runs counter to the union propaganda, you're not going to stay popular for long.

And that just means our kids are just going to keep losing out on the progress they need us to make. What could our schools look like in Seattle if Susan Enfield had been our superintendent these past five years?

Until we are as committed to telling hard truths and making hard changes in our schools as we are to fighting to preserve the status quo, we'll never know. And our kids will keep getting left behind in the crosshairs.