As school starts anew in Seattle, we think of the families still forced apart

/Suddenly it's September. Somehow it's already the end of the first week of school.

Every summer goes by a bit too fast, but this was a special year for our family, so the past few months went by in a blink.

I began a summer-long break from writing at the beginning of June, and soon after that we welcomed a perfect new baby girl into this world. So, less than two weeks into my little hiatus, mom and baby Sojourner were home full-time along with me. In a matter of a few more days, the school year had ended for our two boys, and we were all home together in a little time-space cocoon spun of family ties. It's a rare gift to have such free and uninterrupted time as an entire family, and we made the most of it -- on the road, in the woods, and especially at home together.

So, on Wednesday morning this week, as we celebrated a new school year and greeted the first day with pancakes and extra excitement, it hardly felt like we were getting back into the routine. The morning still had a golden glow to it, and things still felt light and fun. The boys would be gone for but a few short hours and then we'd all be back home again.

First we all walked our oldest three blocks to Emerson for his first day of fourth grade. He was happy and unconcerned. He's been there and done all this several times before. What was there to possibly worry about?

Next, the rest of us drove to Columbia City Preschool to drop Zeke off for his first day of his second year of preschool. Unlike last year, when he was a nervous two-year-old (with a nervous dad) leaving home for the first time, this year found Zeke relaxed and excited to see his friends and teachers again. He was a happy chatterbox on the way there, and we all lingered together during that car ride for a few final moments in the summertime bubble where we'd spent the last couple months -- the fantasy world of endless family time and warm sunshine that felt so safe and real.

The bubble popped, in a way that was both much-needed and super jarring, as we pulled up in front of the preschool. It was as if I'd been feeling around for something in the dark, thinking I was fine and just about to grab it, only to have the lights abruptly flipped on. Turns out I was not where I thought I was! And that's good to know, but it can be disorienting, you know?

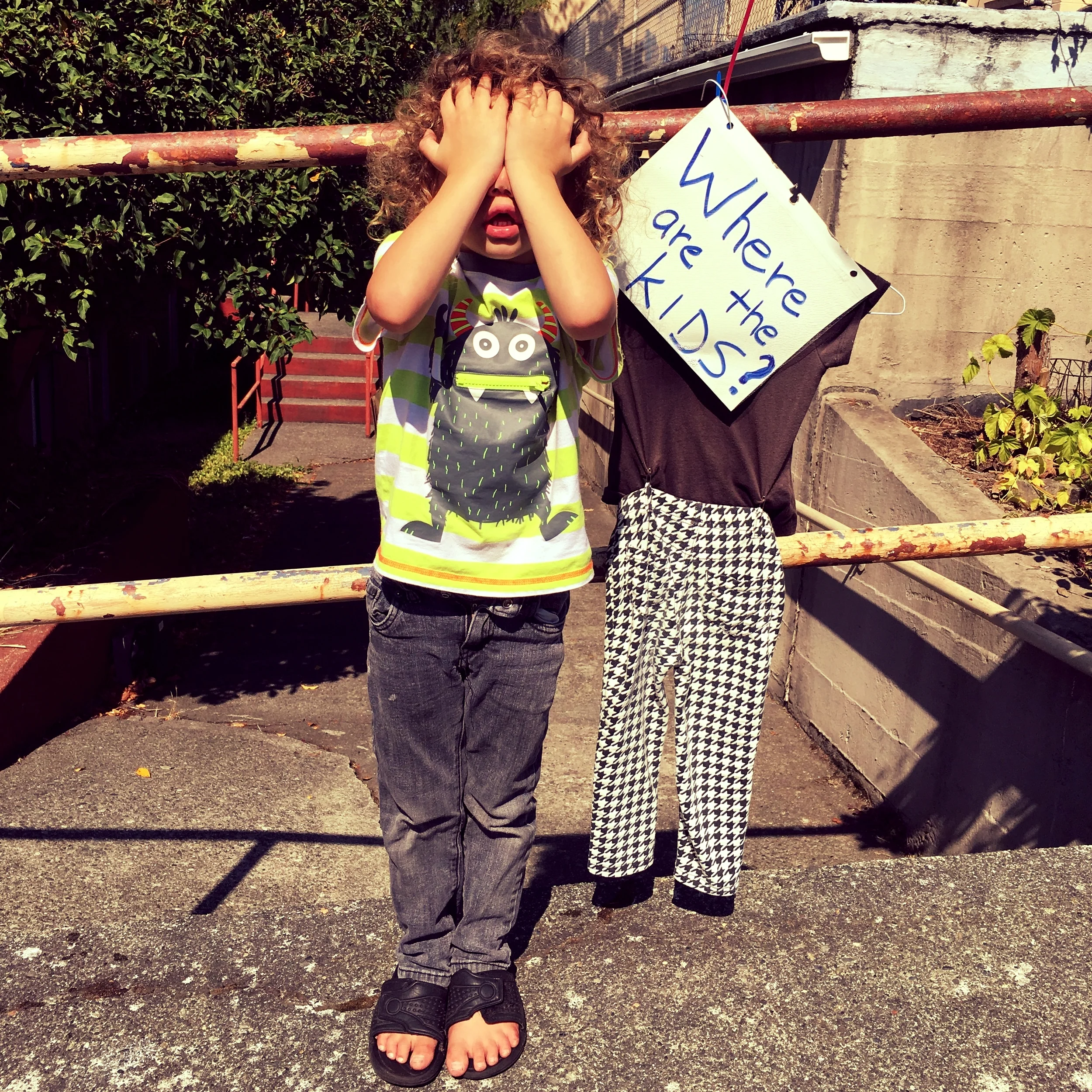

Hanging there outside the school was a sign and a set of toddler-sized clothes on a hanger. "Where are the KIDS?" the sign asked. Actually, it still asks. It's still hanging there. And that, strangely, was the needle, the slap-in-the-face-you-say-thanks-for that punctured my summertime-family-fantasy bubble.

I asked my son to stand and smile for this photo. Instead, he covered his eyes, and it made the picture mean something more to me.

Part of taking time off, I can see now, was about taking time to cover my eyes. Back in early June, I was so fired up about the kids and parents being detained and separated by our government that I could hardly talk about it without erupting. I was overwhelmed, especially in looking at our daughter in her first hours and days of life, with thoughts of the kids and parents who weren't together. I was almost obsessed with thinking of what I would be hoping for if I was a parent separated from my boys, or from this new tiny, helpless, perfect baby.

I was in a bubble this summer, truly, and I still am. We have the luxury of health, (relative) wealth and, above all, time with our children. In June, I pictured in vivid detail having Zeke's hand pulled away from mine for the last time by ICE agents who were just following orders. I couldn't stop imagining the sight of Julian looking back at me, screaming for me to do something, as he was pulled away and around a corner. I thought of my partner losing her grip as baby Soji was ripped from her arms.

I imagined sitting in a cell, alone or with other strangers, with nothing to do but wonder where my kids are. My mind goes to strange terrible places even now, even as my kids are all asleep in warm beds upstairs. Who are they with, I imagined wondering from inside a detention center. What has been done to them? What has been said to them? Have they been sold? Will they still remember and believe that I love them if we never see each other again? How can I live without them?

I imagined feeling alone, knowing I would do anything to see them again, to find them, to try to protect them, but having no outlet for that energy. I imagined hoping and praying desperately for someone else to feel what I was feeling. I imagined needing someone else, someone with privilege and agency, to act as if the best interests of my children and my family were their own.

I would need, captive and helpless in a detention center, for someone to know that this was wrong -- not on a logical level, where you post your opinion on social media or sign petitions or aim for legislation, but on a cellular level. The kind of knowing that our hearts do when they won't let us look away when something isn't right.

These sorts of nightmare-daydream imaginings would fade and leave me wondering if I was this person for someone. By having had the thought, it felt like I had a responsibility I couldn't shake. Who will do something if not me? I couldn't be sure.

Then the old trick worked again. A resolution was resolved, or some such thing, to stop this awful practice of separating families, and a solemn institutional pledge was made with winks and crossed fingers to put an end to the injustice by some concrete future date.

The same thing was done back in December 2016 in Standing Rock, when the government announced that the easement had been denied for the Dakota Access Pipeline. It felt mostly theatrical even at the time, yet most of us took the bait. We took a minute, we took a breath, we took a ride home, and before we knew it, everything was out of hand. The rug had been pulled back out, and it was all over. Trump reversed Obama's stall tactic and the pipeline was completed.

Now, today, weeks past the supposed reunification deadline for the detained parents and children, at least 500 kids are still separated from their families. Hundreds of dads are still banging their heads against painted-white cinder-block walls in detention centers across America, wondering what has happened to the most precious, beloved thing in their world, or searching for them frantically on the outside. Hundreds of mothers are still grieving and alone and less than whole, left waiting and hoping.

The rest of us are still taking our kids to school, still going to work, still living the dream.

Imagine being so desperate that you would risk everything -- even your very freedom -- to bring your family to a place with the possibility of opportunity. Of relative safety. Imagine what it would take for you to uproot your family, or what the circumstances would have to be to cause you to flee not only your home, but your country, and to voluntarily take on these risks and hardships. Imagine the fear you would have to balance knowing you were fleeing to a country that would not openly welcome you.

Imagine the terror you would feel upon being caught, and the desperation, then, of being a mother separated from her frightened young children. Feel yourself being one of those frightened young kids.

I did. I imagined all these things in the early summer, and I pondered them in my heart. I considered and felt the obligation that comes with knowing: if you see a job that needs to be done, then you are the one to do it. If not now, when? If not me, who?

I knew all these things. I felt all these things. And I looked at this new baby, and with fresh eyes at my two boys, and I watched Lindsay being a mother, and I couldn't quite bring myself to think through what would need to be done. It wasn't a conscious thing, looking back, but I was tired, and I wanted to relax and enjoy some time with my family, and when I was offered a way to rationalize doing exactly that, I took it. I let my guard down when we were told immigrant families would no longer be separated, and I sunk snugly into the summertime bubble with my little family and covered my eyes. It was an exercise in privilege.

Then I pulled up to drop Zeke off at preschool Wednesday, and I remembered -- suddenly, abruptly -- what a joyful luxury it is to drop my kids off at school at all. To be just down the hall when they wake up in the middle of the night or there to share breakfast in the morning. To know they are safe and cared for and loved. What a joy just to know them at all.

Our government intentionally separated detained children from their parents, and almost none of us did anything. I myself spent the summer acting like it didn't totally matter because it wasn't my kids.

Sure, this time in the bubble was much needed. Self-care is important, and spending time with the ones you love is never something you regret, and there are lots of good reasons to justify clearing my head and reorienting over the past few months. It was a deep breath well breathed.

But now that thin little summertime bubble has popped. I still remember what life looked like from in there, all safe and cozy and endless, and I know it's not a life everybody is so privileged to lead.

In the case of the children taken from their families and not returned, my life is a dream stolen from them.

How do I live in a way that honors this understanding? What can I do?

I'm not sure, but I'm thinking about it again. Hard. And writing about it, for the first time in three months. If you're here reading, I hope you'll consider these questions with me.

What would we do if these were our own kids? Our own brothers and sisters?

What would we think of folks like you and me, people with good hearts who say they care but continue to just take care of their own kids? What would we think of the people who knew what was happening but chose to stay in the bubble?